Brody enters the hardware store to find yet another disgruntled Amity resident in conversation with the storekeeper. The customer's complaint plays over the scene as Brody walks between the shelves of gardening implements and household tools in search of paints and brushes. On the surface it seems like just some background noise, but in fact it dovetails neatly with two of the movie's intertwining themes: the economic imperative and the basic impulse to survive.

The dissatisfied customer is clearly one of the many islanders who depends on the summer tourists for his livelihood, and, like many such people, he refers to his clients in mildly derogatory terms ('the summer ginks'). His supply chain has been disrupted ('You haven't got one thing on here I ordered. Not a beach umbrella, not a sun lounger, no beach balls.') and the prospect of a financially successful season is under threat ('This stuff ain't going to help me in August.'). The litany of beach accessories - completely innocent in itself - acts as a kind of grim counterpoint given the knowledge that both Brody and the audience possess in much the same way that a neighbour's innocent repetition of the word knife plays on the murderess's guilt in Hitchcock's Blackmail (1929).

The customer's last but incomplete line ('If I can't get service from you, I'll go and get service from -') is later echoed in Larry Vaughn's observation of economic competition ('If the people can't swim here, they'll be glad to swim at the beaches of Cape Cod, the Hamptons, Long Island.'). The movie's pop critique of capitalism appealed to Fidel Castro, who praised the film for its Marxist sympathies in conversation with Francis Ford Coppola.

The brief scene in the hardware store ends with another instance of Brody's clumsiness, cutting to the next scene as a jar of paint brushes crashes onto the shelf.

Monday, October 31, 2011

Main Street

The next scene begins with an exterior shot of an empty street. White picket fencing marks the boundaries of properties on both sides of the road, and the houses that can be seen behind leafy trees are of white clapboard. A branch of pink blossom hangs over the upper left portion of the frame. Brody emerges from a building on the far side of the street, delivering a line of continuity dialogue as he opens the gate. As he begins to march purposefully down the street a cyclist in a blue shirt passes him in the opposite direction. The long shadow he casts in front of him is a reminder that it's still early morning. The camera executes a reverse track to the corner of the street and swivels to follow Brody as he passes a green fire hydrant. Just before the cut to a different angle, Brody breaks his stride with a little skip. As he walks, a sequence of sound effects (a dog barking, birds singing, and the distant sound of a high school band) help to suggest the idyllic nature of the community. The geometric precision of the white fencing and the gleaming white facades are in stark contrast to the twisted broken fencing on the beach. Here at least there is an appearance of harmony and orderliness - even the fire hydrant has been painted in the same colours as the shutters of the houses that line the street.

As Brody passes one of these houses a man in a charcoal suit emerges. Although we do not yet know that this is the medical examiner with whom Brody has just spoken, his sombre clothing - more in keeping with an undertaker than anything - sets him apart from the bright summer imagery that infuses the scene. In contrast, the next character to step out onto the street in Brody's wake is Harry Meadows, the editor of Amity's local newspaper. His powder blue linen suit is at least more in keeping with the season. Intent on his purpose, Brody notices neither of the two men, but their convenient appearance just as he walks by suggests the way in which the Amity grapevine works. As he marches down the slope towards the town's main intersection, Brody is accosted by another elderly resident, one of several seemingly interchangeable old codgers who harry the chief at different moments in the film. On this occasion the complaint is about the karate school kids, but Brody deflects it once again.

In contrast to the almost deserted streets through which Brody has just walked, the town centre is bustling with activity. Cyclists and pedestrians (including a woman in a yellow trouser suit) mill about under a large banner proclaiming the forthcoming Fourth of July celebrations. The sound of a whistle accompanies Brody as he crosses the street, like an echo of the one that summoned him to the grisly discovery on the beach.

As Brody passes one of these houses a man in a charcoal suit emerges. Although we do not yet know that this is the medical examiner with whom Brody has just spoken, his sombre clothing - more in keeping with an undertaker than anything - sets him apart from the bright summer imagery that infuses the scene. In contrast, the next character to step out onto the street in Brody's wake is Harry Meadows, the editor of Amity's local newspaper. His powder blue linen suit is at least more in keeping with the season. Intent on his purpose, Brody notices neither of the two men, but their convenient appearance just as he walks by suggests the way in which the Amity grapevine works. As he marches down the slope towards the town's main intersection, Brody is accosted by another elderly resident, one of several seemingly interchangeable old codgers who harry the chief at different moments in the film. On this occasion the complaint is about the karate school kids, but Brody deflects it once again.

In contrast to the almost deserted streets through which Brody has just walked, the town centre is bustling with activity. Cyclists and pedestrians (including a woman in a yellow trouser suit) mill about under a large banner proclaiming the forthcoming Fourth of July celebrations. The sound of a whistle accompanies Brody as he crosses the street, like an echo of the one that summoned him to the grisly discovery on the beach.

Sunday, October 30, 2011

Coroner's Report

Polly's account of the karate school kids is interrupted by the telephone. She picks up on the first ring and barely gives the medical examiner time to speak before she passes the call to Brody, who, cradling the receiver on his shoulder, acknowledges it with a terse interrogative 'yeah'. He then aligns the report in the typewriter and types the words SHARK ATTACK as the Probable Cause of Death. The scene is lifted directly from the novel, but dispenses with a conversation between the coroner and the police chief that implies a cordial relationship between the two men. In the film the medical examiner is virtually silent - speaking only when directed by the Mayor and voicing opinions that have been foisted on him. Behind his thick-framed Henry Kissinger glasses, the expression on his face shifts as easily as his conscience.

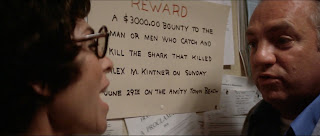

The brief close up of the report in the typewriter tells us that the victim of the attack was a student and that the time of death was estimated at 11.50 p.m. The date is given as 7-1-74, which will prove to be a continuity error in the movie's time line when the second shark victim is attacked on the twenty ninth of June. More immediately noticeable, however, is a spelling mistake: the word coroner has been typed out twice as corner. Unlike the typos in Jack Torrance's manuscript, this is unlikely to be a subtle indication of character, but simply poor spelling from the movie's props department. The report is in any case destined to be thrown away - or amended, as the medical examiner puts it - and the document Hooper consults in the mortuary scene gives 'probable boating accident' as the cause of death.

Polly tries to reassert her position by setting the morning's agenda, but Brody, rising from his desk, interrupts her with a request for 'a list of all the water activities that the city fathers are planning today.' The reference suggests a government of benign patronage and benevolent wisdom and, when the authorities gather to announce the temporary beach closure, it's no surprise that they are made up exclusively of men. In Jaws women are relegated to supporting roles - the caring mother in Ellen Brody, or the grieving one in Mrs Kintner.

As Brody leaves his office, the camera tracks back and then pans with him as he heads for the exit, executing a reverse of the shot that opened the scene. With the exception of the cutaway to show the police report, the whole scene has in fact been filmed in a single take. Brody asks Hendricks about the beach closed signs. The deputy's bewildered response ('We never had any.') prefigures Meadows's comment ('We never had that kind of trouble in these waters.') on the ferry.

Brody pulls on his windcheater and, dodging an elderly resident who has come to complain about illegal parking, makes for the exit. There is a curious detail of wardrobe that is never explained: over his right shoulder Brody is wearing what looks like an orange towel, just as he had in the earlier scenes at home. He pulls his jacket on over it, but this time there is no wife to pull it teasingly from him. It has, at any rate, disappeared by the time he emerges onto the street in the next scene. If there is any reason for this piece of wardrobe, it is never given, and one can only speculate that his character is such a bundle of neuroses that he requires the comfort of a security blanket.

Saturday, October 29, 2011

Wax On Wax Off

Not yet having been brought up to speed on the shark attack, Polly's main concern is the nine year old kids who have been karateing the picket fences. She recounts Amity's latest crime wave in a folksy idiom ('...we got a bunch of calls...') and a comically bewildered tone that is accompanied by an equally comic mime of a karate chop. In contrast to the Amity of Peter Benchley's novel (which is riddled with real violence and corruption), the community in the movie is a cosy place where crime is limited to quirky high jinks of karate vandals or the low level misdemeanors of tourists parking in red zones.

By the mid Seventies the craze for martial arts - kick-started by the twin successes of Enter the Dragon (1973) on the big screen and the David Carradine show Kung Fu (1972 - 1975) on the small - was in full swing. James Bond had already jumped on the bandwagon with an Eastern-themed adventure in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), as had the dying Hammer horror studio in the same year with The Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires. Sam Peckinpah would demonstrate the balletic quality of hand to hand combat in The Killer Elite (1975). The song Kung Fu Fighting by Carl Douglas was a disco hit the year Jaws was being filmed. The popularity of chop-socky cinema at the time helps to put Amity's nine year old vandals in some kind of cultural context, but the association of karate and fences wouldn't be made explicit in American cinema again until the middle of the next decade.

By the mid Seventies the craze for martial arts - kick-started by the twin successes of Enter the Dragon (1973) on the big screen and the David Carradine show Kung Fu (1972 - 1975) on the small - was in full swing. James Bond had already jumped on the bandwagon with an Eastern-themed adventure in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), as had the dying Hammer horror studio in the same year with The Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires. Sam Peckinpah would demonstrate the balletic quality of hand to hand combat in The Killer Elite (1975). The song Kung Fu Fighting by Carl Douglas was a disco hit the year Jaws was being filmed. The popularity of chop-socky cinema at the time helps to put Amity's nine year old vandals in some kind of cultural context, but the association of karate and fences wouldn't be made explicit in American cinema again until the middle of the next decade.

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Let Polly Do The Printing

The next scene - the only one to take place in the Amity police station - opens with a shot of a traumatised Cassidy sitting in the foreground on the left of the frame with Patrolman Hendricks in the background on the right. Each man has a glass of a pale milky liquid in his hand, a mixture no doubt concocted to settle their queasy stomachs. While Cassidy seems unaware of the glass in his hand, Hendricks sips at his like a boy who has been given a soda as a treat. There is the sound of a door opening and closing and Polly - a plump white-haired woman in grey tweed - steps into the room. She addresses Hendricks in a surprised tone, and her greeting ('Well, you're up awful early.') hints at Amity's low crime rate as well as the somewhat folksy nature of its police force. This latter point is reinforced by the woman's character itself, which is quickly established as that of a slightly scatty matriarch. Hendricks motions her towards the sound of typing that is coming from off-screen and Polly marches past a bulletin board on which is pinned an image of the stars and stripes and the legend This Is Our Flag Be Proud Of It.

\

The camera pans with her and tracks behind her as she enters the chief's office. Brody is at his desk, typing. He ignores his secretary's question ('What have you got on today?') and gives her a gentle reminder about the new filing system, suggesting the minor power struggle that exists between them. The camera comes to a momentary halt as Brody and Polly have their initial exchange, and a third of the screen on the left is obscured by the wall and door jamb. As Polly comes around the desk, the camera moves over the threshold to reveal a composition of vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines provided by shadows on the wall, the fixtures and furniture of the interior and the partial view of a pitched roof outside the window. Like the earlier images of the skewed vertical slats of the broken fencing along the beach, the geometry of the frame provides the viewer with a subliminal visual message. The message itself is a contradiction, one that suggests a sense of dislocated order, and it is a concept that will inform both the community's initial attempts to keep the monster at bay and the final improvised strategies employed by the three men who are chosen to hunt it down.

The brief but memorable role of Polly was given to a non-professional actress called Peggy Scott. Like the other locals cast in the movie, she was chosen because she looked and sounded the part. Her delivery gives the dialogue an almost improvisational feel, whilst both the pitch of her voice and her general demeanor look forward to the diminutive ghostbuster played by Zelda Rubinstein in Poltergeist.

Monday, October 17, 2011

You Know How To Whistle, Don't You?

As Brody and Cassidy run towards the sound of the whistle the camera cuts to a reverse angle further down the beach and shows a pair of blue-uniformed legs stagger on a sand dune. With a final shrill blast the owner of the legs collapses into a heap and in close up we see the face of Patrolman Hendricks. He occupies the right side of the screen - just as Brody did when he took the phone call in the kitchen. The crown of his hat is cropped just above the brim by the top of the frame. Over his left shoulder, on which can be seen a blue and yellow patch bearing the Amity Police emblem, is a quadrant of sea. Snaking away behind him to the left of the screen is a tilted section of weather-beaten fencing, and in the distance can be seen six orange and white striped bathing cabins. The expression on the officer's face is either fear or disgust, or both, and - to leave us in no doubt that he has just stumbled upon something unpleasant - a brief ominous music cue plays on the soundtrack. The whistle (attached to a key ring) is still clenched between his teeth and, as he removes it with an almost automatic gesture, he wipes his lower lip with the back of his hand, breaking a thin line of saliva that hints at a recent emetic reaction.

There is a cut to a lateral view of the surf line as Brody and Cassidy arrive at the scene and the camera pans with them as they come to a halt. They remain framed on the left side of the screen between two extended wooden poles that form part of the twisted fence whilst Hendricks kneels on the dune on the right. Brody motions to Cassidy to remain where he is and then advances cautiously towards something out of shot. In the foreground, his head bowed, Hendricks picks up his whistle-cum-key-ring and digs it into the sand like a petulant schoolboy. The sound of seagulls is prominent on the soundtrack almost drowning out the music which continues to play under the scene, now less ominous and almost plaintive.

Having wound the tension up to such a point, Spielberg satisfies our ghoulish curiosity with a close up: a lump of tangled seaweed overrun with scuttling crabs in which the recognisable form of a female hand entangled in hair is upraised as if in a final plea for help. This will, presumably, be the same limb that Hooper examines in the later mortuary scene. The crabs - like the spiders that Indiana Jones brushes off Alfred Molina's back in Raiders of the Lost Ark- seem to hunt in packs. They also seem to be able to fly as one of them drops into the frame (no doubt aided by a wrangler dressing the set) just as Brody utters the words, 'Oh, Jesus.' As the crabs swarm over the grisly flotsam the score incorporates eerie harp figures that seem an echo of the music that accompanied Chrissie's midnight swim.

There is a cut to a medium shot of Brody standing to the left of the frame, the sea beating implacably behind him. He is still clutching the girl's belongings that he has gathered up like a beachcomber - her jeans and top under his arm, his left hand clutching the orange hemp bag. He removes his glasses and turns his head towards the ocean until his eye line connects with the horizon. This visual motif - already established in the shot of Brody's silhouette in the bedroom - establishes him as an observer rather than a participant of the action. There will be two further occasions when he stares out at the expanse of water (before the attack on the Kintner boy and after the attack in the estuary) and only on the second and final occasion - as the camera follows his gaze and pushes out into the ocean - will he make the decision to act.

The beach scene in which Chrissie's remains are discovered was the first scene of the movie to be filmed (in May 1974) and - judging from the mismatched weather patterns alone - it clearly took more than a single day. By a stroke of luck the changing sea and sky contribute a subliminal message. When Cassidy and Brody walk along the beach the sky is blue and the sun sparkles invitingly. In the next moment with the discovery of the body, the sky has become uniformly overcast and the water is a cold slate green. Although it was probably not remarked upon at the time, it was a sign of things to come.

There is a cut to a lateral view of the surf line as Brody and Cassidy arrive at the scene and the camera pans with them as they come to a halt. They remain framed on the left side of the screen between two extended wooden poles that form part of the twisted fence whilst Hendricks kneels on the dune on the right. Brody motions to Cassidy to remain where he is and then advances cautiously towards something out of shot. In the foreground, his head bowed, Hendricks picks up his whistle-cum-key-ring and digs it into the sand like a petulant schoolboy. The sound of seagulls is prominent on the soundtrack almost drowning out the music which continues to play under the scene, now less ominous and almost plaintive.

Having wound the tension up to such a point, Spielberg satisfies our ghoulish curiosity with a close up: a lump of tangled seaweed overrun with scuttling crabs in which the recognisable form of a female hand entangled in hair is upraised as if in a final plea for help. This will, presumably, be the same limb that Hooper examines in the later mortuary scene. The crabs - like the spiders that Indiana Jones brushes off Alfred Molina's back in Raiders of the Lost Ark- seem to hunt in packs. They also seem to be able to fly as one of them drops into the frame (no doubt aided by a wrangler dressing the set) just as Brody utters the words, 'Oh, Jesus.' As the crabs swarm over the grisly flotsam the score incorporates eerie harp figures that seem an echo of the music that accompanied Chrissie's midnight swim.

There is a cut to a medium shot of Brody standing to the left of the frame, the sea beating implacably behind him. He is still clutching the girl's belongings that he has gathered up like a beachcomber - her jeans and top under his arm, his left hand clutching the orange hemp bag. He removes his glasses and turns his head towards the ocean until his eye line connects with the horizon. This visual motif - already established in the shot of Brody's silhouette in the bedroom - establishes him as an observer rather than a participant of the action. There will be two further occasions when he stares out at the expanse of water (before the attack on the Kintner boy and after the attack in the estuary) and only on the second and final occasion - as the camera follows his gaze and pushes out into the ocean - will he make the decision to act.

The beach scene in which Chrissie's remains are discovered was the first scene of the movie to be filmed (in May 1974) and - judging from the mismatched weather patterns alone - it clearly took more than a single day. By a stroke of luck the changing sea and sky contribute a subliminal message. When Cassidy and Brody walk along the beach the sky is blue and the sun sparkles invitingly. In the next moment with the discovery of the body, the sky has become uniformly overcast and the water is a cold slate green. Although it was probably not remarked upon at the time, it was a sign of things to come.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Summertime Blues

Just as Brody asks Cassidy 'You here for the summer?' there is a series of blasts on a whistle from along the beach and the two men start to run towards the sound. Later during the Fourth of July panic scene Brody will vainly try to prevent the lifeguards from raising a similar warning signal ('No whistles! No whistles!'). It's appropriate that the first note of alarm should be cued up by a word that carries specific associations for the community. Its totemic value has already been established by a number of glancing references in the script, but its full symbolic significance will be distilled in Larry Vaughn's economic equation ('Amity is a summer town. We need summer dollars.')

If summer means economic prosperity, then winter - as Quint's reference to welfare in his town hall speech makes clear - is a period of potential recession. The residents of Amity are acutely aware that 'summer's lease hath all too short a date'. Indeed, so valuable are those few income-generating months that time itself becomes a commodity on the island. 'Twenty four hours is like three weeks,' complains the shrewish motel owner when Larry Vaughn announces the temporary beach closure. When trying to negotiate further beach closures, Brody himself will use time as a bargaining chip ('If we make an effort today, we might be able to save August.'). In the hospital scene Vaughn himself will repeat the same month like a desperate mantra of survival until Brody bluntly states, 'Larry, the summer is over.'

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

What's The Angle?

As Brody and Cassidy walk along the top of the dune, the camera - tilted to capture the blue sky streaked with cirrus clouds in the upper half of the frame - tracks along the beach at the base of the slope. Brody carries items of the missing girl's clothing together with an orange hemp handbag with an Inca-type sun motif on it (echoing the sun image on the billboard), and fiddles with a pair of aviator sunglasses. Cassidy, his sweater tied around his waist, holds a length of driftwood in his hands. As they come to the end of the twisted broken fencing and descend the slope onto the beach, each actor executes a small piece of physical business. Brody, testing his shades against the glare of the sun, loses his footing and stumbles. Cassidy, stung by the suggestion that his girl ran out on him, snaps the driftwood in two to punctuate his petulant delivery of the line, 'Look, I reported it to you, didn't I?' Brody's misstep is one of a number of instances that suggest a certain physical clumsiness in the character - later in the hardware store, he knocks over a jar of paint brushes and walking down the corridor to the council chambers he bumps his head against a hanging door sign.

The part of Cassidy was played by Jonathan Filley and it is his only credited role as an actor. He would go on to have a movie career, but as a production manager, not a performer. It was probably a wise choice: the way he snaps the piece of driftwood feels like something done on cue rather than a genuine moment, and, moments later, when called upon to react at the discovery of the girl's remains, he looks frantically about him in an almost pantomime gesture. To be fair, he looks right for the part and his delivery of the line 'I was sort of passed out' carries the appropriate tone of self-centered indifference.

As the two men descend the dune and begin to walk along the beach, the camera swivels round to follow them and then continues to track along the sand with the sea sparkling in the background. Shooting the scene would have required extensive laying of tracks for the camera to run on (this was before the days of the Panaglide camera) and thorough rehearsal of the actors to make sure they hit their marks. Maybe that explains why Filley's snapping of the stick seems slightly wooden - he and Scheider had probably run through the scene countless times to get it right.

Possibly every Spielberg film contains a scene like this - one that involves a single shot, a roving camera and carefully choreographed actors. Orson Welles was a master of this technique, which dispenses with the need for editing whilst retaining a visual dynamic within the frame, and the low angled shot Spielberg uses here is somewhat reminiscent - though not quite as drastic - as those Welles employed in Citizen Kane.

The brief exchange between Brody and Cassidy about their origins ('You an islander?' 'No, New York City.') is the first reference to the notion (already hinted at by the wording of the welcome on the billboard) that Amity is a community unto itself. As one of the residents later says, 'You're not born here, you're not an islander.'

The part of Cassidy was played by Jonathan Filley and it is his only credited role as an actor. He would go on to have a movie career, but as a production manager, not a performer. It was probably a wise choice: the way he snaps the piece of driftwood feels like something done on cue rather than a genuine moment, and, moments later, when called upon to react at the discovery of the girl's remains, he looks frantically about him in an almost pantomime gesture. To be fair, he looks right for the part and his delivery of the line 'I was sort of passed out' carries the appropriate tone of self-centered indifference.

As the two men descend the dune and begin to walk along the beach, the camera swivels round to follow them and then continues to track along the sand with the sea sparkling in the background. Shooting the scene would have required extensive laying of tracks for the camera to run on (this was before the days of the Panaglide camera) and thorough rehearsal of the actors to make sure they hit their marks. Maybe that explains why Filley's snapping of the stick seems slightly wooden - he and Scheider had probably run through the scene countless times to get it right.

Possibly every Spielberg film contains a scene like this - one that involves a single shot, a roving camera and carefully choreographed actors. Orson Welles was a master of this technique, which dispenses with the need for editing whilst retaining a visual dynamic within the frame, and the low angled shot Spielberg uses here is somewhat reminiscent - though not quite as drastic - as those Welles employed in Citizen Kane.

The brief exchange between Brody and Cassidy about their origins ('You an islander?' 'No, New York City.') is the first reference to the notion (already hinted at by the wording of the welcome on the billboard) that Amity is a community unto itself. As one of the residents later says, 'You're not born here, you're not an islander.'

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

It's About Time

As Brody's jeep travels along an empty road, the camera follows it with a pan shot from right to left. The radio is tuned to the local station and as the police vehicle sweeps past there are snatches of the same peppy DJ's voice heard earlier in the bedroom scene. The camera halts on a low-angled shot of a cinema-screen-sized advertisement welcoming tourists to Amity and announcing the island's fiftieth annual regatta. The regatta, incidentally, never makes an appearance in the film, although sailboats featured prominently in the sequel.

The image on the billboard is of a tanned girl in an orange bikini splashing about on a yellow sun lounger. Like Chrissie Watkins, she has long hair and seems to have drifted too far from shore. She looks directly out of the picture, laughing invitingly at the viewer. Two sailboats drift in the background between her and the distant shoreline. In the top left hand corner of the picture a cartoon yellow sun wearing orange-tinted glasses smiles benignly down. The picture has a frame in the same shade of primrose as the Brodys' kitchen.

The billboard provides us with information about time and place, just as the sliding graphics of Psycho anchor the opening of that picture to a precise moment and location. Amity's regatta is due to start on the fourth of July, a resonant date in the American calendar and one around which the action of the film pivots. The image also tells us that the community is dependent on its summer visitors whilst the wording of this public service message ('Amity Island Welcomes You') emphasises the group over the individual.

Interestingly, the narratives of both Jaws and Psycho take place over more or less the same compressed time period of just over a week. Psycho starts on a Friday (11th December) and ends nine days later on a Sunday (20th December) whilst Jaws starts on a Friday (27th June) and ends eleven days later on a Tuesday (8th July). Both films actually play fast and loose with their own time frames. In the penultimate scene of Psycho a wall calendar clearly displays the day's date as the seventeenth, and - with the exception of the Christmas decorations in downtown Arizona in some early plate shots - there is no reference made to the imminent holiday. In fact, the only reason Hitchcock put the date at the start of the picture was to explain away the presence of those street decorations, which had already been put up when the second unit crew filmed background for the studio process shots in December 1959. It would have been too costly to go back and reshoot them in January and it was too late the dress the Bates motel with fairy lights and a Christmas tree (a trick missed by Gus Van Sant in his spooky shot-for-shot remake).

There are a few wormholes in the time scheme of Jaws, as well. According to the report Brody types up, the first attack takes place on the first of July, whilst the second one takes place on Sunday June 29th - a circumstance made doubly impossible by the fact that that date fell on a Saturday in 1974. By the end of the picture any pretence at accuracy is abandoned when Hooper is unable to name the day of the week ('It's Wednesday. It's Tuesday, I think.'). None of this, of course, has any underlying thematic significance although it probably reflects the sense of dislocation experienced by the film cast and crew as weeks of location shooting on Martha's Vinyard stretched into months, and the concept of time began to lose all meaning.

The image on the billboard is of a tanned girl in an orange bikini splashing about on a yellow sun lounger. Like Chrissie Watkins, she has long hair and seems to have drifted too far from shore. She looks directly out of the picture, laughing invitingly at the viewer. Two sailboats drift in the background between her and the distant shoreline. In the top left hand corner of the picture a cartoon yellow sun wearing orange-tinted glasses smiles benignly down. The picture has a frame in the same shade of primrose as the Brodys' kitchen.

The billboard provides us with information about time and place, just as the sliding graphics of Psycho anchor the opening of that picture to a precise moment and location. Amity's regatta is due to start on the fourth of July, a resonant date in the American calendar and one around which the action of the film pivots. The image also tells us that the community is dependent on its summer visitors whilst the wording of this public service message ('Amity Island Welcomes You') emphasises the group over the individual.

Interestingly, the narratives of both Jaws and Psycho take place over more or less the same compressed time period of just over a week. Psycho starts on a Friday (11th December) and ends nine days later on a Sunday (20th December) whilst Jaws starts on a Friday (27th June) and ends eleven days later on a Tuesday (8th July). Both films actually play fast and loose with their own time frames. In the penultimate scene of Psycho a wall calendar clearly displays the day's date as the seventeenth, and - with the exception of the Christmas decorations in downtown Arizona in some early plate shots - there is no reference made to the imminent holiday. In fact, the only reason Hitchcock put the date at the start of the picture was to explain away the presence of those street decorations, which had already been put up when the second unit crew filmed background for the studio process shots in December 1959. It would have been too costly to go back and reshoot them in January and it was too late the dress the Bates motel with fairy lights and a Christmas tree (a trick missed by Gus Van Sant in his spooky shot-for-shot remake).

There are a few wormholes in the time scheme of Jaws, as well. According to the report Brody types up, the first attack takes place on the first of July, whilst the second one takes place on Sunday June 29th - a circumstance made doubly impossible by the fact that that date fell on a Saturday in 1974. By the end of the picture any pretence at accuracy is abandoned when Hooper is unable to name the day of the week ('It's Wednesday. It's Tuesday, I think.'). None of this, of course, has any underlying thematic significance although it probably reflects the sense of dislocation experienced by the film cast and crew as weeks of location shooting on Martha's Vinyard stretched into months, and the concept of time began to lose all meaning.

Monday, October 10, 2011

Exterior Day

The next shot is of the exterior of a white clapboard house in morning sunlight. There is a softness to the quality of the light that is reminiscent of the Cape Cod paintings of Edward Hopper. A tall fence runs from the right of the frame up to the rear porch steps. In fact, it is hardly a fence at all as there are gaps in it big enough to drive a station wagon through. The door opens and first Michael Brody and then his parents emerge. The boy is wearing swimming trunks and carries flippers and a face mask. He scampers down the steps and runs along the side of the house towards the ocean, which can be seen glittering in the background, a single sailboat on the horizon. Brody - now dressed in full uniform - is carrying a coffee mug, and his wife - still in her pale blue nightdress - follows him, tugging at the towel which still hangs around his neck. They execute a kind of dance as they cross the back yard, Brody obligingly turning in a circle to allow his wife to unravel the towel. This moment of choreography suggests the harmony of their relationship, but logically it makes no sense. In the previous scene Brody, still only half dressed, was wearing the towel around his neck, and it's still there when he emerges from the back door. Didn't he think to remove it when he was putting his shirt on?

The exchange between husband and wife is once again playful ('Listen, chief, be careful, will you' 'In this town?') with Ellen following in the tradition of the typical Hawksian heroine by calling Brody by the name of his office. As he climbs into his jeep (framed through another open doorway) Ellen climbs onto the swing where her younger son Sean is still playing. The swing - branded a death trap only seconds ago - has now become a convenient prop for providing a mother and child moment. They wave goodbye and, as Brody reverses out into the road, there is a cut to a wider shot of the house (another Hopperesque image) which places it in the coastal landscape.

Saturday, October 1, 2011

Double Jeopardy

A telephone rings off-screen and the camera pans from left to right as Brody moves across the room to answer it. He picks up the receiver but the line is dead. He mutters something to himself and reaches lower down out of shot for a second receiver. Out of focus and in the background to the left of the screen, Ellen Brody is busy washing away the blood from her son's cut and drying it with kitchen towel. Brody's face in close up occupies the right side of the frame and registers his reaction to what narrative convention tells us must be news of a missing girl. We hear only his side of the exchange ("What do they usually do? Wash up or float, or what?"), which - like the earlier conversation in the bedroom - telegraphs that he is a relatively new member of the community.

Both the action and the composition of the scene serve to establish the relationship between Brody's responsibilities to his family and his responsibilities to the town of Amity. The fact that there are two separate phone lines on the kitchen wall suggests that while there exists a clear division between his private and professional life, the two are not mutually exclusive. The imminent threat to the community now takes precedence (in focus in the foreground) whilst the first small domestic crisis of the day is relegated to a fuzzy background image. Spielberg contrasts action in these two spatial planes at other key points in the movie. When Brody is on the beach anxiously looking towards the ocean for signs of the shark, the head of a local businessman looms distractingly into his view on the right of the frame. During the hunt, the shark rears up out of the chum slick behind Brody (also positioned to the right of the screen) and provides the movie's most celebrated shock . In both these shots it is the action in the background that demands the viewer's attention.

The dialogue between Ellen and her son is mostly indistinct although one line of Michael's that is clearly heard ("Can I go swimming?") provides an explicit link to the foreground action. Brody will, in fact, find it increasingly difficult to protect his own family, and Michael, already marked by blood, will be in the water when two of the shark attacks occur.

Apart from the scene when he types up the report on Chrissie Watkins's death, much of Chief Brody's work (researching the habits of sharks, discussing territoriality with Hooper and recruiting shark spotters) is done from home. In this, the film takes its lead from the novel, which also focused on the domestic setting. With no time for breakfast, Brody leaves the house with a coffee to go and his wife's parting comment ("I want my cup back.") is another small detail that suggests Brody's home life and work life are inextricably linked.

Both the action and the composition of the scene serve to establish the relationship between Brody's responsibilities to his family and his responsibilities to the town of Amity. The fact that there are two separate phone lines on the kitchen wall suggests that while there exists a clear division between his private and professional life, the two are not mutually exclusive. The imminent threat to the community now takes precedence (in focus in the foreground) whilst the first small domestic crisis of the day is relegated to a fuzzy background image. Spielberg contrasts action in these two spatial planes at other key points in the movie. When Brody is on the beach anxiously looking towards the ocean for signs of the shark, the head of a local businessman looms distractingly into his view on the right of the frame. During the hunt, the shark rears up out of the chum slick behind Brody (also positioned to the right of the screen) and provides the movie's most celebrated shock . In both these shots it is the action in the background that demands the viewer's attention.

The dialogue between Ellen and her son is mostly indistinct although one line of Michael's that is clearly heard ("Can I go swimming?") provides an explicit link to the foreground action. Brody will, in fact, find it increasingly difficult to protect his own family, and Michael, already marked by blood, will be in the water when two of the shark attacks occur.

Apart from the scene when he types up the report on Chrissie Watkins's death, much of Chief Brody's work (researching the habits of sharks, discussing territoriality with Hooper and recruiting shark spotters) is done from home. In this, the film takes its lead from the novel, which also focused on the domestic setting. With no time for breakfast, Brody leaves the house with a coffee to go and his wife's parting comment ("I want my cup back.") is another small detail that suggests Brody's home life and work life are inextricably linked.

Vampire

Through the door comes a boy (Michael Brody played by eleven year old Chris Rebello). Smiling, he announces, "Mom, I got cut", and then, holding up his left hand to display a jagged line of blood that runs diagonally across the palm from index finger to wrist, adds, "I got hit by a vampire." A wider shot of the kitchen places Brody to the left of the screen and Ellen to the right. In their reactions both parents immediately conform to the stereotype of father as disciplinarian and mother as carer. While Brody admonishes his son ("You were playing on those swings again, weren't you?"), Ellen steps forward to tend to the cut. When Michael thrusts his palm towards her, Ellen makes light of the incident ("I think you're going to live.") but Brody underlines the potential risk of injury ("Those swings are dangerous."). The parents' reactions establish a pattern for the rest of the movie: the father constantly worrying about lurking danger, the mother carefree (and, in some instances, careless) and confident in the safety of their environment.

Ellen is happy for the children to go swimming the day after the first shark attack and allows Michael to sit in his boat at the dock. She is not unsympathetic to her husband's fears and, when faced with evidence (the picture in the shark book), can be equally authoritative ("Michael? Did you hear your father? Out of the water! Now!"). It is only when her son narrowly escapes death in the Pond (thus fulfilling her prophetic words in the kitchen) that Ellen begins to appreciate the potential threat. By the time her husband sets off on the shark hunt, the roles have been reversed: he makes light of the danger ("Tell them I've gone fishing.") and she exits (both the scene and the movie) in tears.

For their son Michael there is a similar transformation. At the beginning of the movie the only monsters in his world are those of the imagination ("I got hit by a vampire.") and he can smile in the knowledge that they do not really exist. When faced with a real monster, his gaze (directed out at the audience) is of pure terror.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)