Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Day For Night

Just before Chrissie surfaces there is a cut to a low-angled shot of the ocean with the land in the distance. The setting sun is clearly visible just above the horizon under a thin bank of cloud. The use of a wide angle lens creates an effect known as perspective distortion and makes the girl seem impossibly far from the shore. She breaks the surface facing the camera and we briefly glimpse her bare shoulders before she sinks back until her mouth is almost level with the water. She is smiling and gives a couple of excited breaths before she turns her head towards shore and cries out 'Come on in the water.' Susan Backlinie gives a wonderfully nuanced reading of the line, suggesting the girl's puzzlement and frustration that the boy has not followed her. There is a cut to the boy on the shore struggling to remove a shoe. He mutters 'Take it easy' to himself and then loses his balance, collapsing drunkenly onto the wet sand. In the distance there is a mass of low-lying cumulus, illuminated from behind by the setting sun, and -by pure natural coincidence- its shape suggests the dorsal fin of a shark.

Changing cloud patterns from shot to shot are an inevitable result of location shooting and are likely only to be spotted by meteorologists. The fact that the sun moves position can be put down to artistic licence: there was a need to illuminate the beach from Chrissie's perspective and to provide a backlight effect as the boy passes out. Strictly speaking, there should be no sun at all. When Brody types up the report he records the time of death as 11.50 p.m - even on the longest day of the year (June 20th) daylight hours on Marthas Vineyard are from about 4.30 a.m to 7.30 p.m. To add to the confusion the underwater shots of Chrissie swimming on the surface include a bright source of white light, clearly intended to be a full moon.

Clearly some individual shots were captured at sunset during what cinematographers call 'the magic hour', but most of the scene was filmed day for night. Night filming can be both difficult and expensive as it requires powerful lighting and special rates for the crew.

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Million Dollar Mermaid

Chrissie swims out into the bay but, unlike the image of her on the poster, she keeps her head above water as she executes a clumsy crawl stroke. In a wide shot we see how inviting a midnight swim could be: the water has a silvery sheen to it (an effect achieved in post-production as these night scenes were filmed during daylight hours) and the only sounds are of the waves and the occasional bleat of a buoy as it is gently rocked by the tide. On the horizon to the left and the right of the frame there are low masses of land that presumably mark the mouth of a natural harbour. In the middle distance, slightly to the left of centre, is the silhouette of the buoy (looking rather like the RKO tower) canted a few degrees to the right.

Chrissie - a black outline on the surface of the water - is now swimming on her back from the right of the frame and after two strokes she draws her leg towards her and then extends it until it is perpendicular with her body. In synchronised swimming this is a basic position known as the Ballet Leg. With only her head and the extended limb visible, Chrissie slowly sinks below the water, keeping the leg perfectly straight until it is completely submerged.

The shot recalls images of Esther Williams, the star of a series of aquatic MGM musicals (including Million Dollar Mermaid, Neptune's Daughter and Dangerous When Wet). Her underwater acrobatics clearly inspired Julie Adams when she went for a swim in The Creature From The Black Lagoon, and it may have been this scene rather than the original Fifties musicals than gave Spielberg the idea of including the Ballet Leg figure. The shot of Chrissie's long shapely leg extended above the water is mildly erotic - it's almost as if she is teasing the viewer with a glimpse of thigh - but it also serves to deconstruct her from summer girl into shark victim. In the water she has already become simply the collection of body parts (arms, head, leg) that will wash up onto the beach.

The fact that Chrissie can execute a perfect Ballet Leg suggests that she - like Esther Williams - is an experienced and confident swimmer, completely at home in the water. Indeed, the ocean almost seems to call to her when she is seated by the campfire and she turns her head towards it. She even has the traditional long flowing hair of a mermaid.

Chrissie - a black outline on the surface of the water - is now swimming on her back from the right of the frame and after two strokes she draws her leg towards her and then extends it until it is perpendicular with her body. In synchronised swimming this is a basic position known as the Ballet Leg. With only her head and the extended limb visible, Chrissie slowly sinks below the water, keeping the leg perfectly straight until it is completely submerged.

The shot recalls images of Esther Williams, the star of a series of aquatic MGM musicals (including Million Dollar Mermaid, Neptune's Daughter and Dangerous When Wet). Her underwater acrobatics clearly inspired Julie Adams when she went for a swim in The Creature From The Black Lagoon, and it may have been this scene rather than the original Fifties musicals than gave Spielberg the idea of including the Ballet Leg figure. The shot of Chrissie's long shapely leg extended above the water is mildly erotic - it's almost as if she is teasing the viewer with a glimpse of thigh - but it also serves to deconstruct her from summer girl into shark victim. In the water she has already become simply the collection of body parts (arms, head, leg) that will wash up onto the beach.

The fact that Chrissie can execute a perfect Ballet Leg suggests that she - like Esther Williams - is an experienced and confident swimmer, completely at home in the water. Indeed, the ocean almost seems to call to her when she is seated by the campfire and she turns her head towards it. She even has the traditional long flowing hair of a mermaid.

Monday, August 29, 2011

Zoetrope

Chrissie runs along the top of the sand dune with the boy in pursuit, the low angled camera tracking them both. The girl races out of the frame just as she cries out the word 'Swimming!' When the boy stumbles for the first time there is a cut to a second faster tracking shot of Chrissie, who, ignoring his pleas for her to slow down, takes off her blue windcheater and tosses it to the ground. There is a cut to a tighter tracking shot of the boy as he calls out 'I'm not drunk' and then the camera is back following Chrissie. Without breaking stride, she lifts her right foot to remove a sneaker. As she looks back laughing there is another cut to the boy. He is now running on flatter ground between two rows of sagging fences. His cry of 'I'm coming' is slightly muffled as he struggles to remove his sweater. There is a cut to Chrissie also removing her sweater before she runs topless away from the camera. The boy's repeated cry of 'I'm definitely coming' carries an obvious sexual connotation: his drunken pursuit of the girl is a kind of clumsy foreplay that ends with his tumbling uncontrollably down the slope of the dune into the white surf - an action, taken together with his repeated line of dialogue, that could be seen as a kind of premature ejaculation. Chrissie is seen as a naked wide-hipped silhouette racing into the sea, which glistens in the moonlight.The camera cuts back to the boy on the beach, still struggling with his sweater. He totters in the surf, trying to remove a shoe, laughing and speaking to himself.

The chase along the sand dune is executed with verve and economy through a combination of cutting and camera movement. After the first establishing shot neither of the characters appear in the same frame, thus emphasising the nature of the pursuit. By shooting the characters through the slats of the fence Spielberg was able to give an additional dynamism to the shots. Just as still images seen through the slits of a spinning zoetrope can give the impression of movement, so figures in motion filmed through vertical gaps can appear to be moving faster than they actually are. John Milius used a similar technique (which he acknowledged he had learnt from watching Kurosawa's samurai movies) for the opening attack of Arab horsemen in The Wind and the Lion.

Spielberg also manages some sleight-of-hand with clever cutting. We see Chrissie remove one shoe and so there is no need to show her take off the second. As she runs down to the beach she is still wearing her denims but when the camera cuts back to her seconds later she is naked. Strictly speaking the time that elapses between the two shots of her (one partially clothed, the other naked) would not be enough for her to struggle out of a pair of tight-fitting jeans, but of course it's totally irrelevant.

Editing allows a film maker to expand or compress time to suit their needs. Next time you watch a movie involving a time bomb (the Fort Knox climax in Goldfinger, for example) count down the seconds from the first shot of the clock and you'll see what I mean. Spielberg had fun stretching out of tension in the climax of the opening scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark, deliberately elongating the jungle creeper Indy clings to and slowing down the closing tomb from shot to shot. Here he was exaggerating editing technique to get a laugh, but in Jaws he used it to propel the narrative forward without snagging it on unnecessary details.

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Goofing Off

Before Chrissie reaches the top of the slope there is a cut to a low angle shot of the sand dune. A dilapidated fence curls along its spine and the background sky is full of glowering clouds. In contrast to the warm golden light of the campfire scene, the image is dominated by shades of grey and charcoal. The girl's silhouette appears on the seaward side of the fence. She pauses briefly and looks back to make sure that the young man is still in pursuit. The outline of his figure can be seen at the far left of the screen several yards behind her. Strictly speaking this arrangement of the two figures at the beginning of the chase along the dune is an error of continuity. In the previous shot both characters ran up the same slope and should have emerged at the top together on the landward side.

Since the advent of video, identifying continuity errors has become the film buff's equivalent of trainspotting. One website lists two hundred and forty one continuity errors (or goofs) for Jaws - ranging from camera reflections and mismatched costumes to spelling mistakes and rearranged furniture. Given the nature of the filming process - and, in particular, the process of filming Jaws - it isn't surprising that the movie should contain so many little flaws - mistakes which are so insignificant that they can only be exposed by multiple viewings when combined with a degree of obsessive-compulsive behaviour.

In rearranging the positioning of the two characters at the top of the sand dune, Spielberg was prepared to forego literal continuity for a visual image that conveyed a sense of the girl's flirtatiousness. Her backward glance is a tease, as is the way she replies to the boy's two questions ("What's your name again?" and "Where are we going?") in an excited rising intonation. She wants him to pursue and ultimately catch her, and her later cry of "Come on in the water" betrays a slight sense of exasperation that he has not followed her.

Since the advent of video, identifying continuity errors has become the film buff's equivalent of trainspotting. One website lists two hundred and forty one continuity errors (or goofs) for Jaws - ranging from camera reflections and mismatched costumes to spelling mistakes and rearranged furniture. Given the nature of the filming process - and, in particular, the process of filming Jaws - it isn't surprising that the movie should contain so many little flaws - mistakes which are so insignificant that they can only be exposed by multiple viewings when combined with a degree of obsessive-compulsive behaviour.

In rearranging the positioning of the two characters at the top of the sand dune, Spielberg was prepared to forego literal continuity for a visual image that conveyed a sense of the girl's flirtatiousness. Her backward glance is a tease, as is the way she replies to the boy's two questions ("What's your name again?" and "Where are we going?") in an excited rising intonation. She wants him to pursue and ultimately catch her, and her later cry of "Come on in the water" betrays a slight sense of exasperation that he has not followed her.

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

Eye Contact

The two shots (underwater POV and beach tracking shot) that play under the opening titles set the scene, and the film's narrative only properly begins after the credits are over. Spielberg uses a classic shot reverse shot to establish the connection between Cassidy and Chrissie. The camera ends its lateral tracking movement and frames the young man slightly to the left of centre of the screen. He is staring intently over his raised cup, his gaze directed off to the right. He inhales on a cigarette and as he blows out the smoke there is a cut to a medium close up of a young woman, partially obscured by a white vapour at the bottom of the screen. She is framed slightly to the right whilst her gaze is focused a little to the left. The positioning of the two characters (each occupying the space into which the other is staring) provides a perfect eyeline match. In a classic shot/countershot they exchange a flirtatious smile, and the young man indicates his intention to make a move by draining his cup. The sound of a sea bird momentarily distracts the woman and, as she turns her gaze away from the man and looks to her left, there is a cut to a wide shot of the entire campfire scene.

We can see the pale margin of surf only a few yards away and beyond that the darkness of the ocean, which we already know from the opening POV shot contains danger. The camera looks down on the scene from the top of a grass covered sand dune, the slope of which occupies the lower right hand corner of the frame. The thin slats of a fence snake up the slope in an irregular pattern.

The cut from close up to wide shot reveals that the two characters are separated by a distance of several feet, the woman excluding herself from the social circle around the campfire. The young man gets up and goes over to her, kneeling down beside her. Between them is a large metal bin that is either smoking or steaming, and we realise that the vapour obscuring the first shot of the woman came from this source and not from the man's cigarette. A short dialogue occurs, but the camera remains atop the dune and we do not hear the exchange. Suddenly the woman gets up, turns towards the camera and runs up the slope with the young man in pursuit.

We can see the pale margin of surf only a few yards away and beyond that the darkness of the ocean, which we already know from the opening POV shot contains danger. The camera looks down on the scene from the top of a grass covered sand dune, the slope of which occupies the lower right hand corner of the frame. The thin slats of a fence snake up the slope in an irregular pattern.

The cut from close up to wide shot reveals that the two characters are separated by a distance of several feet, the woman excluding herself from the social circle around the campfire. The young man gets up and goes over to her, kneeling down beside her. Between them is a large metal bin that is either smoking or steaming, and we realise that the vapour obscuring the first shot of the woman came from this source and not from the man's cigarette. A short dialogue occurs, but the camera remains atop the dune and we do not hear the exchange. Suddenly the woman gets up, turns towards the camera and runs up the slope with the young man in pursuit.

Campfire Tales

In Jack London's short story "To Build a Fire", a nameless prospector in the snowy Yukon is deserted by his dog when his attempts to build a fire in the wilderness fail. By 1908, the year the story was published in its final form, the campfire was well established in American literature as a symbol of the pioneering spirit. From the Leatherstocking novels of James Fenimore Cooper to the folksy horror of Stephen King, tales told around the campfire have always hinted at the threat that lies somewhere out in the darkness. Indeed, in ghost stories - such as the one John Houseman tells at the beginning of The Fog - the campfire itself is often identified as a potential danger, attracting the attention of whatever danger lurks in the wilderness. A campfire encourages people to sit around it in a circle, a symbol of harmony, and, by temporarily providing both light and warmth, it gives the illusion of safety.

In Jaws the circle of teenagers arranged around the fire is broken up by gaps (just as some of Amity's fences are), and the interaction within in the group (some clearly identified as couples, others superficially arranged in pairs) suggests that this is an improvised community. Although Cassidy (Jonathan Filley) makes up part of the circle, he sits with his back to the group and directs his gaze away from the fire. His later conversation with Chief Brody on the beach will identify him as an Islander although he no longer lives on the island; in effect, he is of the community of Amity without being a part of it.

Tellingly, Chrissie (Susan Backlinie) sits outside the group. Early versions of the screenplay made it clear that she was a stranger, a fact that is only implied in the finished script by the description of her as "a summer girl". That no one comes forward to challenge the doctored coroner's report or to collect her remains for burial suggests that she is an outsider, and, as such, her death can be easily swept under the carpet. Indeed, she seems already consigned to the garbage by her association with the detritus - a wooden packing crate and cardboard boxes - that has been discarded around her. She is also sitting to the right of a large metal bin, which resembles one of the steaming try-pots in which Quint boils the flesh off shark jaws. When Cassidy gets to his feet in a wide shot that reveals the complete geography of the scene we see that he has been sitting beside a battered metal beer barrel, a container that will later indicate the presence of the shark. Were these artfully arranged props placed there with a purpose, or is it too fanciful to read into them some element of predestination?

In Jaws the circle of teenagers arranged around the fire is broken up by gaps (just as some of Amity's fences are), and the interaction within in the group (some clearly identified as couples, others superficially arranged in pairs) suggests that this is an improvised community. Although Cassidy (Jonathan Filley) makes up part of the circle, he sits with his back to the group and directs his gaze away from the fire. His later conversation with Chief Brody on the beach will identify him as an Islander although he no longer lives on the island; in effect, he is of the community of Amity without being a part of it.

Tellingly, Chrissie (Susan Backlinie) sits outside the group. Early versions of the screenplay made it clear that she was a stranger, a fact that is only implied in the finished script by the description of her as "a summer girl". That no one comes forward to challenge the doctored coroner's report or to collect her remains for burial suggests that she is an outsider, and, as such, her death can be easily swept under the carpet. Indeed, she seems already consigned to the garbage by her association with the detritus - a wooden packing crate and cardboard boxes - that has been discarded around her. She is also sitting to the right of a large metal bin, which resembles one of the steaming try-pots in which Quint boils the flesh off shark jaws. When Cassidy gets to his feet in a wide shot that reveals the complete geography of the scene we see that he has been sitting beside a battered metal beer barrel, a container that will later indicate the presence of the shark. Were these artfully arranged props placed there with a purpose, or is it too fanciful to read into them some element of predestination?

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

The Kid Stays In The Picture

The credit for the movie producers appears as the camera tracks past a gap in the figures seated in the foreground and through the gap two girls can be seen sharing a joint. The producers' names are in the same reverse alphabetical order as in their company logo, but Richard Zanuck has now sandwiched the letter D between his first name and surname. Perhaps the inclusion of this middle initial (D for Darryl, after his father) is a homage to earlier Hollywood producers such as David O. Selznick and Louis B. Mayer. In comparison with his partner's exotic sounding moniker, David Brown's name seems quite ordinary.

The camera continues its steady tracking shot. We see the back of a young boy in a white beach hat. He is sitting next to a girl in pigtails, who rocks briefly forward as if in laughter. In the background a smiling girl is holding a large lobster intended for the pot. The director's name appears just before the camera comes to a halt on a medium close up of a handsome blond youth, drinking from what appears to be a paper coffee cup and smoking a cigarette. He is sitting with his back to the group around the fire and is framed slightly to the left of centre, staring intently at a point off to the right.

The storyboard for the credit sequence (which can be viewed as one of the extras on the 30th anniversary DVD) names the director as Stevie Spielberg. It's unlikely, however, that he ever intended to use the shortened boyish form of his first name in the opening titles, and this may just have been an affectionate in-joke. True, he did take both producing and directing credit as Steve Spielberg on the war movie Escape To Nowhere, but he made that when he was thirteen years old.

That's not to say that he had completely put away childish things by 1974. There are plenty of shots of him fooling around on set, and he was - according to movie legend - one of the enthusiastic participants in a massive food fight that broke out between cast and crew one evening. Scriptwriter John Byrum (who would go on to direct Richard Dreyfuss in Inserts) was invited to do an early rewrite of the Jaws script, but declined the offer after a meeting with Spielberg, during which the director flew a remote-controlled toy helicopter around his office to a soundtrack of James Bond music.

Spielberg was not much older than the kids sitting around the camp fire in that opening scene, but he was already something of a seasoned pro in the business. One of his early professional assignments was directing Joan Crawford - another seasoned pro, if ever there was one - in a segment for the pilot of the TV show Night Gallery, and he went on to direct a number of experienced television actors such as Dennis Weaver, Martin Landau and Peter Falk. Jaws would prove to be his toughest assignment to date and, perhaps recognising what he had let himself in for, he even tried to bail out of the job at the eleventh hour. Fortunately, Richard Zanuck was on hand to give him some fatherly advice. "This is the opportunity of a lifetime," he said. "Don't fuck it up." The rest, as they say, is history.

The camera continues its steady tracking shot. We see the back of a young boy in a white beach hat. He is sitting next to a girl in pigtails, who rocks briefly forward as if in laughter. In the background a smiling girl is holding a large lobster intended for the pot. The director's name appears just before the camera comes to a halt on a medium close up of a handsome blond youth, drinking from what appears to be a paper coffee cup and smoking a cigarette. He is sitting with his back to the group around the fire and is framed slightly to the left of centre, staring intently at a point off to the right.

The storyboard for the credit sequence (which can be viewed as one of the extras on the 30th anniversary DVD) names the director as Stevie Spielberg. It's unlikely, however, that he ever intended to use the shortened boyish form of his first name in the opening titles, and this may just have been an affectionate in-joke. True, he did take both producing and directing credit as Steve Spielberg on the war movie Escape To Nowhere, but he made that when he was thirteen years old.

That's not to say that he had completely put away childish things by 1974. There are plenty of shots of him fooling around on set, and he was - according to movie legend - one of the enthusiastic participants in a massive food fight that broke out between cast and crew one evening. Scriptwriter John Byrum (who would go on to direct Richard Dreyfuss in Inserts) was invited to do an early rewrite of the Jaws script, but declined the offer after a meeting with Spielberg, during which the director flew a remote-controlled toy helicopter around his office to a soundtrack of James Bond music.

Spielberg was not much older than the kids sitting around the camp fire in that opening scene, but he was already something of a seasoned pro in the business. One of his early professional assignments was directing Joan Crawford - another seasoned pro, if ever there was one - in a segment for the pilot of the TV show Night Gallery, and he went on to direct a number of experienced television actors such as Dennis Weaver, Martin Landau and Peter Falk. Jaws would prove to be his toughest assignment to date and, perhaps recognising what he had let himself in for, he even tried to bail out of the job at the eleventh hour. Fortunately, Richard Zanuck was on hand to give him some fatherly advice. "This is the opportunity of a lifetime," he said. "Don't fuck it up." The rest, as they say, is history.

Monday, August 8, 2011

Nobody Knows Anything

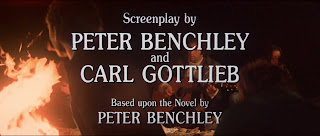

The screenplay credit - which appears over the image of a boy roasting something in the camp fire - names only two of the script's many contributors: Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb. Benchley, whose surname has alphabetical superiority, is listed above Gottlieb, and he is afforded a further 'Based upon the Novel by' credit in a smaller font at the bottom of the screen.

The credit links the two men with the conjunction 'and' and that might suggest the screenplay was a work of collaboration, the two men sitting across a shared desk, bouncing ideas off each other and coming up with one final agreed text. This was, after all, the chosen method of great screen collaborators Billy Wilder and I.A.L Diamond, who lent their own working practices to the characters of Joe Gillis and Betty Schaefer in Sunset Boulevard. Alfred Hitchcock also saw the writing of the screenplay as a collaborative process, and, even though he never took a screenwriting credit, he helped to shape the scripts of his movies through extended story conferences with a variety of scriptwriters.

In the case of Jaws, however, Benchley and Gottlieb were never even in the same room, let alone at the same desk. Perversely, according to modern Hollywood convention, the presence of the word 'and' in a screenwriting credit is an indication that the writers have worked on the project separately. Only if their names are joined by an ampersand (&) does it mean that they worked as equal partners.

When Benchley signed away the movie rights, a clause in the contract gave him the right to produce his own version of the screenplay. There is a final draft credited to the novelist online, and - particularly in the first act - it contains whole scenes and some lines of dialogue that made it into the final movie. For the most part though, it is an uneven and clunky piece of work. The characters are unappealing and their speech patterns seem forced and unnatural. Here, for example, is Larry Vaughn speaking to Brody about keeping the beaches open: "I just want you aware of what you're doing before you tinker with the life blood of all those sage and discriminating souls who elected you."

Carl Gottlieb, whose experience in improv had given him an ear for dialogue, was able to convey more meaning in shorter sentences ("Amity is a summer town. We need summer dollars."). On location, he recorded the lines improvised by the actors in rehearsals and then worked them into the script - the most famous example being the bigger boat quip, which Roy Scheider came up with. Dreyfuss also improvised bits of business (crushing the Styrofoam coffee cup), and Shaw, who was a published novelist and playwright, produced his own version of the Indianapolis speech.

The exact authorship of the Jaws screenplay has been disputed over the decades, each and every contributor providing their own Rashomon-like perspective on the creative process. Playwright Howard Sackler, who was briefly hired to do a rewrite on the strength of his dramatic craftsmanship and his knowledge of scuba diving, supposedly made it a condition of his contract that he would not receive any credit. Was this an act of genuine modesty, or was he simply protecting his Pulitzer-prize-winning reputation? John Milius - Spielberg's macho-movie director buddy - contributed ideas and dialogue over the telephone. His most imaginative contribution to the movie, however, seems to have been in his retrospective and highly selective memories of what he wrote. Spielberg says he himself wrote his own version of the script over one weekend - just as he had read Benchley's original manuscript over two days - but it seems none of the director's ideas for big scenes (including Quint roaring with laughter at a matinee showing of Moby Dick at Amity's local cinema) made it onto the screen.

Discounting the actors' contributions, a total of at least seven people can lay claim to having written part of the Jaws script. It's unlikely that we'll ever really know who wrote what, but, given William Goldman's much quoted aphorism about the trade of screenwriting, maybe it's best not to.

The credit links the two men with the conjunction 'and' and that might suggest the screenplay was a work of collaboration, the two men sitting across a shared desk, bouncing ideas off each other and coming up with one final agreed text. This was, after all, the chosen method of great screen collaborators Billy Wilder and I.A.L Diamond, who lent their own working practices to the characters of Joe Gillis and Betty Schaefer in Sunset Boulevard. Alfred Hitchcock also saw the writing of the screenplay as a collaborative process, and, even though he never took a screenwriting credit, he helped to shape the scripts of his movies through extended story conferences with a variety of scriptwriters.

In the case of Jaws, however, Benchley and Gottlieb were never even in the same room, let alone at the same desk. Perversely, according to modern Hollywood convention, the presence of the word 'and' in a screenwriting credit is an indication that the writers have worked on the project separately. Only if their names are joined by an ampersand (&) does it mean that they worked as equal partners.

When Benchley signed away the movie rights, a clause in the contract gave him the right to produce his own version of the screenplay. There is a final draft credited to the novelist online, and - particularly in the first act - it contains whole scenes and some lines of dialogue that made it into the final movie. For the most part though, it is an uneven and clunky piece of work. The characters are unappealing and their speech patterns seem forced and unnatural. Here, for example, is Larry Vaughn speaking to Brody about keeping the beaches open: "I just want you aware of what you're doing before you tinker with the life blood of all those sage and discriminating souls who elected you."

Carl Gottlieb, whose experience in improv had given him an ear for dialogue, was able to convey more meaning in shorter sentences ("Amity is a summer town. We need summer dollars."). On location, he recorded the lines improvised by the actors in rehearsals and then worked them into the script - the most famous example being the bigger boat quip, which Roy Scheider came up with. Dreyfuss also improvised bits of business (crushing the Styrofoam coffee cup), and Shaw, who was a published novelist and playwright, produced his own version of the Indianapolis speech.

The exact authorship of the Jaws screenplay has been disputed over the decades, each and every contributor providing their own Rashomon-like perspective on the creative process. Playwright Howard Sackler, who was briefly hired to do a rewrite on the strength of his dramatic craftsmanship and his knowledge of scuba diving, supposedly made it a condition of his contract that he would not receive any credit. Was this an act of genuine modesty, or was he simply protecting his Pulitzer-prize-winning reputation? John Milius - Spielberg's macho-movie director buddy - contributed ideas and dialogue over the telephone. His most imaginative contribution to the movie, however, seems to have been in his retrospective and highly selective memories of what he wrote. Spielberg says he himself wrote his own version of the script over one weekend - just as he had read Benchley's original manuscript over two days - but it seems none of the director's ideas for big scenes (including Quint roaring with laughter at a matinee showing of Moby Dick at Amity's local cinema) made it onto the screen.

Discounting the actors' contributions, a total of at least seven people can lay claim to having written part of the Jaws script. It's unlikely that we'll ever really know who wrote what, but, given William Goldman's much quoted aphorism about the trade of screenwriting, maybe it's best not to.

Saturday, August 6, 2011

DOP

Immediately after the film's editor gets her credit and just as the music is reaching a crescendo, the image cuts to a beach campfire scene. The camera now moves left to right in a slow tracking shot to reveal a tableau of young couples. A boy playing a harmonica (which, together with a strummed guitar, provides the scene's source music) sits near but not with a long-haired girl, who exhales a plume of cigarette smoke with the quick nervousness of an unpractised smoker.

The credit for the film's director of photography - Bill Butler - appears as the camera tracks past a kissing couple silhouetted against the orange flames of the fire. The scene is lit like one of those Dutch paintings illuminated by candlelight. The faces of the people sitting in the background glow in the warm amber light whilst the couples in the foreground are in dark silhouette. As DOP (or DP, if you prefer),Butler would have had responsibility for lighting this scene and for burnishing the image with a slightly soft focus. He had worked with Spielberg twice before (including the 1972 TV movie Something Evil) and his work on Jaws would be bookended by contributions to two other iconic Seventies movies - The Conversation in 1974 and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest in 1976.

It was Butler who had the idea of shooting most of the Orca scenes with a hand-held camera - not to give it a shaky cinema-verite look, but to use the camera operator's body to counteract the pitch and roll of the ocean. The camera operator in this case being Michael Chapman, who would go on to work as DOP on Raging Bull. There were other technical challenges to be faced: filming day-for-night scenes on and under the water, using a specially constructed waterproof box to house the camera for the unnerving shots at water level, and, of course, making sure that the shark appeared in the frame but the mechanical equipment that operated it did not.

The credit for the film's director of photography - Bill Butler - appears as the camera tracks past a kissing couple silhouetted against the orange flames of the fire. The scene is lit like one of those Dutch paintings illuminated by candlelight. The faces of the people sitting in the background glow in the warm amber light whilst the couples in the foreground are in dark silhouette. As DOP (or DP, if you prefer),Butler would have had responsibility for lighting this scene and for burnishing the image with a slightly soft focus. He had worked with Spielberg twice before (including the 1972 TV movie Something Evil) and his work on Jaws would be bookended by contributions to two other iconic Seventies movies - The Conversation in 1974 and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest in 1976.

It was Butler who had the idea of shooting most of the Orca scenes with a hand-held camera - not to give it a shaky cinema-verite look, but to use the camera operator's body to counteract the pitch and roll of the ocean. The camera operator in this case being Michael Chapman, who would go on to work as DOP on Raging Bull. There were other technical challenges to be faced: filming day-for-night scenes on and under the water, using a specially constructed waterproof box to house the camera for the unnerving shots at water level, and, of course, making sure that the shark appeared in the frame but the mechanical equipment that operated it did not.

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

POV

The first image of the movie (which starts at 00:00:45 as the opening credits continue) is an unremarkable view of a rocky sea bed. The camera moves through the water as small fish dart across the screen from left to right. It grazes over a crop of vermicelli-like seaweed, brushes past the brownish fronds of another salt water plant and then seems to bury itself into another growth of stringy weed. The water is dappled with a pale light.

The combination of the visual image and the threatening ostinato music on the soundtrack makes it clear that the camera is, in effect, the shark moving almost blindly through the water. Spielberg could have opened his picture with cleverly edited inserts of a real Great White (as Michael Anderson did in Orca the Killer Whale), or he could have teased the viewer with a fin cutting through the water (as Danny Boyle chose to do in The Beach). Instead, he used the point of view shot.

POV shots are the equivalent of first person narratives in fiction, but, unlike novels, films rarely maintain them over an entire story. When they do - as in Robert Montgomery's 1946 version of Raymond Chandler's The Lady in the Lake - they seem more gimmicky than involving. A more considered and more effective use of the technique was in Rouben Mamoulian's erotically-charged interpretation of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1931), which contains a bravura transformation scene shot from the main character's point of view. Indeed, the POV shot is a staple of horror films such as Halloween and The Shuttered Room where it is used to mask the identity of the killer.

It was partly this tradition that inspired Spielberg to adopt the technique, but mostly it was done out of that mother of invention, necessity. Pre-production storyboards and on set photos suggest that it was the original intention to include shark 'money shots' much earlier in the movie. Spielberg ended up not showing the shark because it refused to perform on cue, and, quite frankly, because it looked a bit rubbish. When we do finally get to see it in close-up - rearing up out of the ocean to take its final victim in its jaws - we're so caught up in the story that we don't notice its rubber teeth bending as they bite down on a screaming Quint.

The combination of the visual image and the threatening ostinato music on the soundtrack makes it clear that the camera is, in effect, the shark moving almost blindly through the water. Spielberg could have opened his picture with cleverly edited inserts of a real Great White (as Michael Anderson did in Orca the Killer Whale), or he could have teased the viewer with a fin cutting through the water (as Danny Boyle chose to do in The Beach). Instead, he used the point of view shot.

POV shots are the equivalent of first person narratives in fiction, but, unlike novels, films rarely maintain them over an entire story. When they do - as in Robert Montgomery's 1946 version of Raymond Chandler's The Lady in the Lake - they seem more gimmicky than involving. A more considered and more effective use of the technique was in Rouben Mamoulian's erotically-charged interpretation of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1931), which contains a bravura transformation scene shot from the main character's point of view. Indeed, the POV shot is a staple of horror films such as Halloween and The Shuttered Room where it is used to mask the identity of the killer.

It was partly this tradition that inspired Spielberg to adopt the technique, but mostly it was done out of that mother of invention, necessity. Pre-production storyboards and on set photos suggest that it was the original intention to include shark 'money shots' much earlier in the movie. Spielberg ended up not showing the shark because it refused to perform on cue, and, quite frankly, because it looked a bit rubbish. When we do finally get to see it in close-up - rearing up out of the ocean to take its final victim in its jaws - we're so caught up in the story that we don't notice its rubber teeth bending as they bite down on a screaming Quint.

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Mother Cutter

That Verna Fields gets a full screen credit to herself in the opening titles is an acknowledgement of her contribution to the picture. Not only would she go on to win an Academy Award for her work, but she would also rise rapidly to the upper echelons of Universal Studios management, accepting the position of Feature Production Vice President. There was even talk of her co-directing Jaws 2 when that movie ran aground in the initial stages of production.

Fields accepted the plaudits and the praise with equanimity. "I got a lot of credit for Jaws, rightly or wrongly," she told the Los Angeles Times in 1982. By then Spielberg's picture had already been anointed a modern classic and the stories surrounding its epic troubled production were part of Hollywood legend. One of the most commonly repeated stories was that Verna Fields had single-handedly saved the picture in the editing suite, and the story was repeated enough for it to start being reported as fact. In 1995 screenwriter Carl Gottlieb felt compelled to scotch this rumour in a letter to The New York Times:

"Speaking from first-hand knowledge and without denigrating Verna Fields's enormous contribution to Jaws, that film didn't need saving. As the screen writer who was present on location and during post-production [...], I remind you that the movie was made by a young, accomplished, confident Steven Spielberg, whose body of work speaks for itself [...] every frame of film an editor cuts is conceived and shot elsewhere, by others. Jaws was the production of a fruitful and happy collaboration, and Steven Spielberg is the true auteur of that experience."

Verna Fields, who died from cancer in 1982, would not have disputed this. Editing is about shaping and refining material, not creating it. As the ellipses in square brackets in the text above show, I have edited Carl Gottlieb's original text, but all the words are his. Fields did, nevertheless, play a much more collaborative role on Jaws than would normally be expected of a film editor. She was there on location and - like Hooper and Brody in the Fourth of July scene - was in constant contact with the director via walkie-talkie, relaying requests for specific shots.

One undisputed contribution that Fields made to Jaws was the loan of her swimming pool as an improvised location for Spielberg's eleventh hour decision to shoot an insert of Ben Gardener's head (complete with one wormy eye socket) popping out of the shattered hull of his sunken boat. In a way, it's a perfect metaphor for the relationship between the director and the editor: Spielberg came up with the idea and Fields provided the pool.

Monday, August 1, 2011

Der Dum Der Dum Der Dum

By the time the credit "Music by John Williams" appears on the screen, the simple repetition of two notes (F and F sharp) performed in a low register on a cello have already established the presence of the shark. When Williams first played the theme to Spielberg on the piano, the director - who himself is a fairly accomplished musician - thought he was kidding around. His first instinct was to dismiss the idea as too simple, but when he heard it again he knew that they were on to something.

The musical terminology for the "Jaws Theme" is ostinato, which comes from the Italian word meaning stubborn or obstinate. In rock and roll, it's known as a riff, the repetitive hook that makes a song like The Knack's My Sharona so irresistible. Essentially, Williams's two note theme is a musical expression of the single-mindedness of the shark, and its very lack of complexity means that it can be put through innumerable permutations. In the opening credits the two notes are first heard separately, spaced out by an ominous silence. They then come together and gather speed, just as a shark might move towards its victim. By varying the tempo, Williams was able to suggest both lurking menace and savage ferocity.

In the liner notes to the original soundtrack album Spielberg compared Williams to Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Bernard Herrmann, two titans of classic Hollywood scoring. Indeed, there are some structural similarities between Williams's Main Title and Herrmann's iconic Psycho music - both employ a driving figure for strings overlaid with a strained melody. Similarly, the piratical music (a combination of hunting bugles and swashbuckling figures) that accompanies the Orca chasing the barrels is reminiscent of the scores that Korngold provided for Errol Flynn.

Two composers that Spielberg does not mention, however, are Igor Stravinsky and Claude Debussy. If you listen to The Rite of Spring and La Mer you can hear the influences. Williams was, in fact, following in the Hollywood tradition of mining the classics for thematic material, and he would go on to plunder Holst and Haydn for Star Wars, even lifting passages from Stravinsky for the Tatooine desert scenes. This is not in any way a criticism of his contribution to film scoring, which is more about selecting the appropriate music for a scene than composing it afresh. Williams's instincts for Jaws were spot on - you only have to play his theme against any shot of water to realise how effective his idea was.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)